#i just remember a distinct mistrust of Childe the WHOLE TIME

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

thoughts on how Liyue Archon quest went [3]

Kaeya and Lumi break amber on Mt Hulao and get yelled at by Mountain Shaper. that was a thing, right? Mountain Shaper and Moon Carver kinda got ignored a lot when it came to the Adepti, ngl. like tbf, i know why Cloud Retainer and Xiao got attention, but still,,, like Moon Carver was cool b/c Beeg Deer(tm) but Mountain Shaper??? bro got sidelined so hard man.

anyway, Mt. Aocang, yah? Total Side Tangent Moment(tm): i always liked the seats that alluded to Guizhong (b/c i love Guizhong lore, she's Very Silly(tm)), and i remember this part very well the first time i did this quest b/c i was also very curious on who Guizhong was. it was just interesting to me that, despite being gone for so long, she showed up in the narrative due to her importance to Liyue? and i just thought that that was so cool... i should ramble abt Guizhong at one point, b/c i'm so interested in her as a character despite her being Deceased(tm).

SIDE TANGENT OVER

when they go into Cloud Retainer's abode, i like to see this as a true testament to Lumine's skills in puzzles. i love Smart Lumine(tm) so fuckin much, and it's always my favorite when puzzles are involved. b/c i see it going down like: Paimon: these mechanisms are so confusing.... Kaeya: i mean, i feel like they're doable, but ffs it's convoluted Lumi: proceeds to completely upend the puzzle in like seconds there we go Kaeya: Paimon: Kaeya: wow, we got a show off here huuuh? (inwardly, he's simping)

after talking w/ Cloud Retainer, obviously they get back to Serious Mode(tm) and get back and yap to Childe. and obviously they give Childe and update, and he gives them an update, and there's still no trust Childe: dw guys, i can help u out, i just gotta find someone Lumi: uh huh. really? Childe: yep. anyway, stay alive till we see each other again! leaves Lumi: sus. Kaeya: sus. Paimon: what DOES THAT MEAN?!?!?

#genshin headcanons#kaelumi#kaeya genshin impact#lumine genshin impact#brain worms#guys listen#smart Lumine#is my favorite#i think normal thoughts#i swear i do#also the entire time i was doing this quest#i just remember a distinct mistrust of Childe the WHOLE TIME#like if u guys liked Childe from the get go#go off#ur a chad#but me personally#weird ass mf#i wouldn't trust him as far as i could throw him#and that's not far b/c i'm weak baby#i would apologize for the Childe slander#but#sus#granted#just b/c i dont like him#doesn't mean lumi and kaeya end up disliking him#there's a lot there#which i have to take time to explain#if u've read all these tags#i worry for ur mental health

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcanon time!

I want Alvin to feel very disconnected from Elympios upon returning “home” because he barely remembers the place and what he does remember is kinda dated through the lens of a child and a little idealised, like simply “going home” would solve everything. No one ever pings him as anything but Elympion but his accent sounds just a little off from having very specific and limited influences growing up, so sometimes he sounds very urban Trigleph but some words he says in a particularly posh accent and others don’t, and he has no idea of the distinction until he’s able to see for himself. He doesn’t really feel like he belongs in Elympios, especially since he holds no connection to his family, but he can’t really consider himself Rieze Maxian either. So he’s kind of stuck in the middle and X2’s desire to break down the barriers between the countries would resonate?

I do want him being as surprised with the current technology as everyone else is, because when he was a kid stuff like GHSes were basically still landlines. I kinda want him chatting with Ludger about Ludger’s childhood so he can get a feeling for how life has progressed in Trigleph

(Only to realise Ludger knows pretty much nothing besides the technology aspects because of Julius, both in the sense of “Julius would explain GHS stuff to him while it was first in development” and “Ludger never really felt the need to have a social life outside of his brother and high school”)

But mostly I want to write him figuring out Julius is Bisley’s son (or at least the son of an aristocratic family) before Ludger does, because it’s a real big missed opportunity that could have connected X1 and X2 a little more as well as give a non-Jude, non-Milla character a plot-relevant connection to Ludger

Also I think Alvin and Julius would mutually understand the whole “ex-child soldier who mostly cut ties with the rest of their blood family except for one (1) person who is their sole motivation for the cruelty they commit and is constantly putting up facades, leading others to mistrust them because of their lies” thing.

(Damn it, Ludger deserves to have a crisis about if the nerdy big brother Julius that he remembers is the ‘real’ Julius who is very okay with murder.)

Also want Alvin to be faced with questions about Elympios and sometimes being like “Dude I don’t know, I lived here when I was six years old, what did you know about Rieze Maxia when you were six?”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanksgiving

The first "thanksgiving" happened in October of 1621, but the constructed history and significance of that event has been over 500 years in the making. When I was a child I liked Thanksgiving because it meant family time. When I became a man I felt angered and betrayed by the truth of the holiday. Now, as a father, I see Thanksgiving as a teachable moment - a chance to properly frame the history of the day while still enjoying time with my two boys, my wife, and my family. Holidays are a wonderful chance to remember where we come from, what is important to us, and how we got where we are. Mark Twain is attributed as saying something to the effect of "history doesn't actually repeat itself, but it often rhymes." Thanksgiving gives us a lot of opportunity to reflect on this.

In order to better understand the first Thanksgiving, we start nearly 100 years earlier in the 1530s. The King of England, Henry VIII, wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (she was the first of what would end up being six wives), but the Pope wouldn't allow it. So the King declared that the Pope was no longer the head of the church. This set England on a path that renounced Catholicism in favor of the Church of England as the ultimate religious authority, and set the King as the head of that Church. 100 years later, it was not acceptable in England to be any sort of Christian other than as part of the Church of England.

The King of England was a powerful man who may have usurped a religion to get what he wanted. The religious intolerance of England back then echoes to recent times as strife between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland. And while today England is full of people who are allowed to practice other religions, it is interesting that in 1620 the pilgrims to America were the "wrong kind" of Christian to be in England. (Perhaps there will always be "wrong kinds" and "others" in our society, and perhaps the test of our virtue isn't in the certainty of our beliefs, but in our tolerance for alternatives.)

Intolerance was a problem for the group of Christians who would become the Pilgrims, and that intolerance ran both ways. They wanted to be separate from the Church of England, and to worship in their own way. But such dissent would not be tolerated and they were persecuted. So they fled England and moved to Holland where there was some acceptance for differences in religion. However, these separatists didn't like their children learning dutch and adopting dutch culture. They found it hard to integrate with Dutch society while retaining strict adherence to their own specific religious and cultural doctrine. So the decided they needed to move again.

The Separatists were immigrants in Holland, but without the willingness to integrate they could not make Holland their home. They themselves were intolerant of their new host country. England wouldn't tolerate them. They wouldn't accept Holland. And they refused to change themselves. Their self-imposed isolation led them to the idea that they could be left alone in America, and land with no King, to do as they pleased... and they intended to establish a new society based on their specific and strict religious and cultural beliefs.

So they worked out a deal with England (and I am simplifying this a bit). England would give them passage to America, where they would prosper and work off the debt for this passage by sending surplus back to England, to the profit of the investors. Because of this, the Pilgrims weren't the only people on the Mayflower. With them were indentured servants they forced to come along, and some "company men" who were responsible for seeing to the financial success of the colony. In their journals, the pilgrims referred to these people, with whom they would have to live and work, as "the strangers".

So the forces that brought the pilgrims to America were both religious and financial. Here was a group of people divided between those seeking to create and spread their idea of a religious haven, and those who wanted to make money.

Fortunately the obvious conflict came to a head early, and before they stepped off the boat to start their new colony they wrote and signed the Mayflower Compact, which established a secular government for the colony. The leadership for the colony would not rest in religion, but would be shared by all. Well... not all... 41 men signed, out of the 101 total passengers on the ship. Women, indentured servants, and children were not given authority to participate in the compact and did not sign it.

But this story isn't just about Pilgrims, it's also about the New World: America, and the people who already inhabited it. While it's likely Norse sailors (specifically Leif Ericson around 1003) were the first Europeans to North America, Christopher Columbus is the most well known. Ponce de Leon was the first to reach what would become the United States. These explorers and those that followed brought with them horrible epidemics of disease, for which the native population had no defenses. Not only were their immune systems unprepared for the new diseases, they had no experience or medicine for treating these new illnesses. There is no conclusive estimate of the population of Native Americans living in what would become the United States before European explorers arrived, but credible attempts have estimated a population as low as 2 million, and as high as 18 million. Similarly, we can't know how many died to disease, but we do know that whole villages disappeared after the arrival of the Europeans. And we know that by 1900 there were only about 250,000 Native Americans left. Which means that 400 years after Europeans arrived, the population of Native Americans was reduced by somewhere between 90 and 99%, with some tribes disappearing entirely.

When the first settlers started to arrive, they weren't coming to an empty continent. They were coming to a place where people had been living for thousands of years. They had trails, and traded with one another. They had separate and distinct cultures and languages. They had specialized skill sets and industries. But now they were all being devastated by unrelenting waves of epidemic disease and war brought by visitor after visitor looking to exploit the resources of the new world. Those that survived smallpox were still vulnerable to measles, and plague, and new variants of influenza. Imagine wave after wave of disease killing half or more of the population over and again. Those who didn't die still got sick. Who gathered the food? Who tended to the ill? It was devastating to the people, and their cultures. Their infrastructure crumbled, their population reduced, and their way of life was decimated. The effect of such devastation to the psyche of a people is beyond imagining.

And so it was when the Mayflower arrived 130 years after the first explorers. On their first two expeditions ashore the pilgrims found graves, from which they stole household goods and corn - which they would plant in the spring. On their third expedition they encountered natives, and ended up shooting back and forth at each other (bows versus muskets). The Pilgrims decided they didn't want to settle in this area, as they had likely offended the locals with their grave robbing and shootout, so they sailed a few days away. They found cleared land in an easily defended area and began their settlement. This fantastic location was no happy accident. Just three years previous this place was called Patuxet, now abandoned after a plague killed all of its residents. The Pilgrims will say they they founded Plymouth, but it might be more accurate to say they resettled Patuxet.

By the time the Pilgrims found Patuxet it was late December, and they huddled in their ship barely surviving the brutal, hungry first winter. By march only 47 souls survived, though 102 had left port 6 months before.

There were, roughly, three different groups of local Natives. They had been watching the pilgrims carefully all winter, just as the pilgrims had been watching them. In the days before there had been frightening encounters between pilgrims and natives, and the pilgrims were rushing to install a cannon in their emerging fortification. They were on high alert, and expecting confrontation. Given the history, mutual fear, and mistrust, a violent encounter between the two groups seemed imminent and unavoidable.

The story many of us were told is that Squanto and a group of Indians approached the pilgrims, as if neither had ever seen the other before, and in greeting Squanto raised his hand and said, "How". The actual truth is that a visiting chief named Samoset strode, alone, into the middle of the budding and militarizing pilgrim town and said, "Welcome Englishman." And then he asked for a beer. (Truth.) It turns out Samoset was visiting local Wampanoag chieftain Massasoit, and he spoke some broken English, which he had learned from the English fishermen near his home. He took it upon himself to open negotiations with the new settlers. He told them about the local tribes, and brokered an introduction to Chief Massasoit, with whom the pilgrims ultimately signed a treaty.

Along with the treaty came Squanto, a Native American originally from the now defunct Patuxet tribe. Squanto was invaluable to the Pilgrims. Not only could he act as a translator, but he also knew the local tribes and the area itself. It was where he grew up. He knew what food was available, what crops to plant and how, and he knew not only the language but the disposition and history of local tribes. Speaking with the locals isn't enough if you can't discern their desires and motives. Squanto was a great friend to the English Pilgrims, and acted in their interests, sometimes to his own peril.

How did Squanto learn English language and culture? Squanto had been kidnapped by the English captain Thomas Hunt in 1614. Hunt abducted 27 natives, Squanto among them, which he sold as slaves in Spain for a small sum. These hostilities, just years before the arrival of the Pilgrims, are the reason for the initial animosity and aggression toward the English Pilgrims when they arrived, and why the natives were wise enough to attack the English, even if their bows were not a match for English muskets. Exactly how Squanto survived in the old world, or how he got from Spain to England, is unclear. It is known that a few years after his abduction, Squanto was "working" (likely as an indentured servant) for Thomas Dermer of the London Company. Dermer brought Squanto back to the location of the Patuxet village in 1619 as part of a trade and scouting venture, but the village had been wiped out by disease. After acting as translator and negotiator for Dermer on that trip, the now homeless Squanto stayed in America and went to live with Pokanoket tribe. The terms of this arrangement are not clear. It is possible Squanto was a prisoner of the Pokanoket, and that he was "given" in a trade that allowed the Dermer to exit a dangerous situation. Regardless, Squanto chose to live out the rest of his life with the Pilgrims in his childhood home of Patuxet, now renamed Plymouth by the (re-)colonizing English Pilgrims. Whatever the exact details, Squanto was one of the most traveled men in the area - having been born in America and spending time in Spain, England, and Newfoundland.

Squanto's time with the pilgrims appears full of adventures. He was sent as an emissary for peace and trade on behalf of the pilgrims to numerous tribes. It also appears he leveraged his influence among the Europeans to make some of his own demands from these tribes, which drew the ire of many local tribal leaders. Chief Massasoit even called for Squanto's execution. When William Bradford (Plymoth's Governor) diplomatically refused, Massasoit sent a delegation to retrieve Squanto from the Pilgrims. Again Bradford refused, even when offered a cache of beaver pelts in exchange for Squanto, with Bradford saying, "It was not the manner of the English to sell men's lives at a price”. Squanto was very valuable to the Plymoth colony, but he died in 1622 of "Indian fever".

In October (most likely) of 1621 the Pilgrims celebrated their first harvest. The was indeed a harvest feast attended by 90 Native Americans and 53 Pilgrims. Both groups brought food and games to the three day celebration. But this was not the start of the Thanksgiving holiday in America. It was a harvest festival, and harvest was common ground that both cultures celebrated. The American holiday of Thanksgiving was first celebrated as such when George Washington and John Adams declared days of thanksgiving during their presidencies. This was followed by a long period where subsequent Presidents did not declare such events. A writer and editor named Sarah Hale, most famous for penning "Mary Had a Little Lamb", began to champion the idea of a national "Thanksgiving" holiday in a 17 year campaign of newspaper editorials and personal letters written to five different Presidents. Perhaps because of her insistence and the popularity she garnered for the idea, Abraham Lincoln revived Thanksgiving as a unified national holiday in 1863. A few years later Congress enshrined it as a national celebration on the 4th Thursday of November.

And this is my Thanksgiving. It's not the simpleton's story of an awkward greeting followed by a good meal. It's the story of a King who wanted a divorce, religious self-righteousness, the greed of men, a clash of cultures, a struggle for survival, loyalty and betrayal, the creation of a national holiday intended to help mend a nation torn apart by civil war, and the myths we created to tie us all together. As always, truth is a much more engaging and explanatory than a politely shared fiction.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joining the Game Late: S3E10 “Mhysa”

Synopsis

All hell breaks loose at the Twins. Sansa’s still not allowed to curse. Tywin takes the credit for the Red Wedding in the middle of a Lannister family breakdown. Old Nan taught Bran how to tell stories for maximum foreshadowing effect. Walder Frey and Roose Bolton twirl their mustaches while Roose’s son dines on some prime sausage that’s totally not what you think. Yara is so moved by the sight of her brother’s penis that she sets off to be a hero. Sam and Bran compare notes on their plotlines before parting. Davos takes a shine to Gendry and rescues him, only to escape punishment because Melisandre’s fire found the main plot. Arya takes her first vengeance, and Jon has a bad breakup with Ygritte. Shae’s still with Tyrion, but probably not for long. Jaime and Jon have significant homecomings under not so great circumstances, and the show remembers Dany exists just in time for her to crowd surf through her big white savior moment.

Commentary

Like the two previous season finales this one comes off feeling pretty cluttered, except this time even more so. As far as climaxes go the Red Wedding is a comparatively more localized event than the succession crisis and Ned’s execution or the Battle of the Blackwater, and on top of that this season covers only around half a book so its ending lacks much of a natural finality. There is some to be had, like in the sweeping away of the Starks, the two paralleled homecomings by Jaime and Jon, or Bran heading north of the Wall, but this is noticeably more of a midpoint than an ending. Some characters are just left dangling for later seasons, like Theon and his sister (you have no idea how hard it was for me to avoid a BDSM joke with the former...and I get the impression I’m going to have to keep resisting that impulse going forward), or Arya who at the moment seems like she’s going to spend each successive season roaming the countryside and learning how to kill more effectively. I’m not even sure what to make of Stannis being the only ruler to rally to the Night’s Watch call for aid; it really has more to do with what the Lord of Light actually is and wants (thanks, lore and history extras) than anything connected to Stannis’s character. As much as I’ve enjoyed the push and pull between what he wants and what Melisandre wants him to do his personal agency has notably diminished this season and I’m not sure I like it.

All this I’m getting out of the way now, because I need to talk about Daenerys - for longer than she appears in this episode, but for her this is more like a summation of her whole storyline thus far. It’s certainly been...something. For two seasons now GoT has been sort of coasting with Dany, padding her thin plotlines with new material in some places and stretching them out across multiple episodes in others. She’s not the only character given this kind of treatment *coughs*Theon*coughs*, but since she’s so geographically removed from the other events in the show the audience is likely to treat her story as a more distinct element. That’s not a good thing, because at this point it isn’t doing a good job of standing on its own. Season 2′s Qarth storyline wasn’t so bad; it had some good character moments for Dany and Jorah and was punctuated by a strong resolution. Season 3 started Dany off on a big note with her conquest of Astapor and acquisition of the Unsullied, but after that it spent something like five episodes waffling around outside of Yunkai and splitting up its climactic action sequence and this hour’s resolution, in which a crowd of former Yunkish slaves exalt Dany in near-worship for freeing them offscreen somehow because three guys invaded their city and opened it up to an army. Racial optics aside this ending has too many missing pieces leading up to it to feel entirely earned; had the whole Yunkai story been collapsed into two or three episodes at most and there been a stronger connection between the setup and the payoff (maybe, I don’t know, bring out that slaver again so he can be made to grovel and surrender and/or get roasted to death?). Nope, her special ops force backdoors the city and I guess all the slavers are dead now with no other casualties because that’s how sieges work.

The events of Yunkai do however give me the opportunity to talk some more about Daenerys’s motivations and how to fit her present actions into her dictatorial, war crime-laden future. Last season I praised the scene between Dany and Jorah where she admits that she can’t trust anyone (including him) and is able to back up that mistrust with multiple concrete examples. Dany remembers how her brother used and her and how the Dothraki turned on her, and she knows well that she has no allies in Westeros because the people over there are too busy killing each other to care that her roundly hated father still has one living child. It’s therefore not surprising to me that she builds up her follower base by liberating slaves; not only are they numerous and untapped as a political resource in her current surroundings, but Dany believes she can trust in their loyalty because they owe their lives and their freedom entirely to her. The former slaves of Yunkai call her “Mhysa” (”Mother”), drawing an immediate connection to her maternal bond with her dragons who are also unconditionally loyal if not exactly free-willed in the same sense as a free man who has never known slavery. She’s got those in her retinue as well, but they’re loyal to her out of either love/lust (Jorah and Daario along with his mercenary army) or fealty to her late father and disdain for the two men who sat on the Iron Throne after him (Barristan). This interpretation of her methodology may be cynical, but it aligns well with how we know she reacts to people who do not act sufficiently grateful in response to what she perceives to be her kindness (ex. the witch from Season 1) and also foreshadows her descent into Mad Queen-dom once in Westeros. I think there’s also a bookend here with Margaery’s charity work in Flea Bottom in the first episode of the season. Both women - and it is perhaps notable that they are women - are performing good works in service to the unfortunate and the downtrodden, but they’re doing so in a publicly visible way that endears them to the masses and increases their political clout. Daenerys the Breaker of Chains is just a more extreme version of Margaery currying the favor of the people of King’s Landing, and it’s a reminder that in the darkly political world they inhabit honor and compassion are as much tools as anything else.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

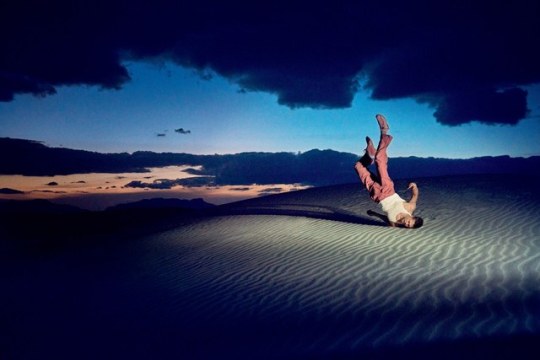

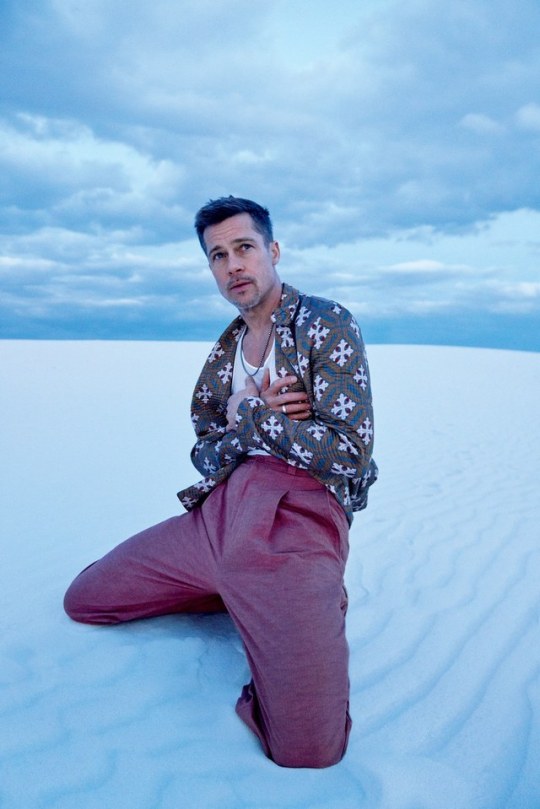

The Everglades, White Sands, and Carlsbad Caverns. PHOTOGRAPHS BY RYAN MCGINLEY Brad Pitt Talks Divorce, Quitting Drinking, and Becoming a Better Man by Michael Paterniti VIDEO

“Summer is coming and, in America, that means it’s time to hit the national parks. So we took Brad Pitt and photographer Ryan McGinley tumbling across three of them: The Everglades, White Sands, and Carlsbad Caverns. Then we sat down with Pitt at home in L.A. for a raw conversation about how to move forward after things fall apart.

Brad Pitt is making matcha green tea on a cool morning in his old Craftsman in the Hollywood Hills, where he's lived since 1994. There have been other properties in other places—including a château in France and homes in New Orleans and New York City—but this has always been his kids' “childhood home,” he says. And even though they're not here now, he's decided it's important that he is. Today the place is deeply silent, except for the snoring of his bulldog, Jacques.

Pitt wears a flannel shirt and skinny jeans that hang loose on his frame. Invisible to the eye is that sculpted bulk we've seen on film for a quarter-century. He looks like an L.A. dad on a juice cleanse, gearing up to do house projects. On the counter sit some plated goodies from Starbucks, which he doesn't touch, and some coffee, which he does. Pitt, who exudes likability, general decency, and a sense of humor (dark and a little cockeyed), says he's really gotten into making matcha lately, something a friend introduced him to. He loves the whole ritual of it. He deliberately sprinkles some green powder in a cup with a sifter, then pours in the boiling water, whisking with a bamboo brush, until the liquid is a harlequin froth. “You're gonna love this,” he says, handing me the cup.

Serenity, balance, order: That's the vibe, at least. That's what you think you're feeling in the kitchen of Brad Pitt's perfectly constructed, awesomely decorated abode. Outside, children's bikes are lined up in the rack; a blown-up dragon floatie bobs on the pool through the window. From the sideboard, with its exquisite inlay, to the vase on the mantel, the house exudes care and intention. And it carries its own stories, not just about when the Jolie-Pitts were a happy family, but also from back in the day, when Jimi Hendrix crashed here. It's said he wrote “May This Be Love” out in the grotto, with its waterfall (Waterfall / Nothing can harm me at all…). “I don't know if it's true,” says Pitt, “but a hippie came by and said he used to drop acid with Jim back there, so I run with the story.”

And yet Pitt is the first one to acknowledge that it's been chaos these past six months, during what he calls a “weird” time. In conversation, he seems absolutely locked in one moment and a little twitchy and forlorn in the next, having been put on a journey he didn't intend to make but admits was “self-inflicted.” The unfortunate worst of it surfaced in public this past September. When he was on a flight to Los Angeles aboard a private plane, there was a reported altercation between Pitt and one of his six children, 15-year-old Maddox. An anonymous phone call was made to the authorities, which triggered an FBI investigation (ultimately closed with no charges). Five days later, his wife, Angelina Jolie, filed for divorce. By then, everything in Pitt's world was in free fall. It wasn't just a public-relations crisis—there was a father suddenly deprived of his kids, a husband without wife. And here he is, alone, a 53-year-old human father/former husband smack in the middle of an unraveled life, figuring out how to mend it back together.

And yet the enterprise known as Brad Pitt inexorably carries on. In November, the movie Allied came out, starring Pitt and Marion Cotillard. At the premiere he was described as “gaunt,” and rumors of an affair with Cotillard, and an on-set encounter between her and Jolie, had been so virulent that Cotillard took to social media to deny them, underscoring her love for her own partner, with whom she was pregnant with their second child. Meanwhile, Pitt's production company, Plan B Entertainment, found itself winning an astonishing third Oscar for Best Picture, with Moonlight. (Pitt spent the Oscars ceremony at a friend's house.) This month Netflix will release Pitt's War Machine, a satire based on the incidents surrounding the firing of General Stanley McChrystal. In the film, he plays a gruff, ascetic stand-in for McChrystal, General Glen McMahon, with both big-gestured comic panache and an oblivious unknowingness that seems to be a metaphor for the entire American war effort.

But on this overcast spring morning, catching Pitt at this flexion point, I would say he seems more like one of those stripped-down Samuel Beckett characters, in a blank landscape, asking big questions of a futile world. Even the generalities he employs for protection seem metaphoric. (He mentioned his estranged wife's name only once, when referencing her Cambodia movie, First They Killed My Father, telling me, “You should see Angie's film.”) The loneliness of this new life, he said, is mitigated by Jacques, who spent most of the interview beached in a narcoleptic reverie at my feet, snoring and farting. (“Did you ever have the uncle that came over with emphysema, and had to sleep in your room when you were 6?” he says. “That's Jacques.” And then: “Come here, boy. Friends for life!”)

When I ask Pitt what gives him the most comfort these days, he says, “I get up every morning and I make a fire. When I go to bed, I make a fire, just because—it makes me feel life. I just feel life in this house.”

GQ Style: Let's go back to the start. What was it like growing up where you grew up? Brad Pitt: Well, it was Springfield, Missouri, which is a big place now, but we grew up surrounded by cornfields—which is weird because we always had canned vegetables. I never could figure that one out! Anyway, ten minutes outside of town, you start getting into forests and rivers and the Ozark Mountains. Stunning country.

Did you have a Huck Finn boyhood? Half the time. Half the time, yeah.

How so? I grew up in caves. We had a lot of caves, fantastic caverns. And we grew up First Baptist, which is the cleaner, stricter, by-the-book Christianity. Then, when I was in high school, my folks jumped to a more charismatic movement, which got into speaking in tongues and raising your hands and some goofy-ass shit.

So were you there for speaking in tongues? Yeah, come on. I'm not even an actor yet, but I know… I mean the people, I know they believe it. I know they're releasing something. God, we're complicated. We're complicated creatures.

So acting came out of what you saw in these revival meetings? Well, people act out. But as a kid, I was certainly drawn to stories—beyond the stories that we were living and knew, stories with different points of view. And I found those stories in film, especially. Different cultures and lives so foreign to mine. I think that was one of the draws that propelled me into film. I didn't know how to articulate stories. I'm certainly not a good orator, sitting here telling a story, but I could foster them in film.

I remember going to a few concerts, even though we were told rock shows are the Devil, basically. Our parents let us go, they weren't neo about it. But I realized that the reverie and the joy and exuberance, even the aggression, I was feeling at the rock show was the same thing at the revival. One is Jimmy Swaggart and one is Jerry Lee Lewis, you know? One's God and one's Devil. But it's the same thing. It felt like we were being manipulated. What was clear to me was “You don't know what you're talking about—”

And it didn't fuck you up? No, it didn't fuck me up—it just led to some eating questions at a young age.

The best actors blur into their characters, but given how well the world knows you, it seems you have a much harder time blurring these days? I have so much attached to this facade. [gestures]

But then, in War Machine, you find the little gesture that makes the Glen McMahon character ours. Like the way he runs, which is hilarious. The run to me was important because it was about the delusion of your own grandeur, not knowing what you really look like. All pencil legs, you know. Not being able to connect reality to this facade of grandeur.

The other equally distinctive characteristic is Glen's voice. Where did it come from? You know, it's a little bit of a cliché, but I just enjoyed it too much: There's, you know, of course, Patton in it. But I could not get Sterling Hayden out of my mind. I'm just fascinated with Sterling Hayden, off-camera, between films, and I couldn't escape that. There's even a little bit of Chris Farley in mannerisms. And then Kiefer Sutherland in Monsters vs. Aliens, you know, doing the cartoon voice. It just wouldn't go anywhere else; it kept coming back there.

Have you ever felt the need to be more political? I can help in other ways. I can help by getting movies out with certain messages. I've got to be moved by something—I can't fake it. I grew up with that Ozarkian mistrust of politics to begin with, so I just do better building a house for someone in New Orleans or getting certain movies to the screen that might not get made otherwise.

You're good at playing that kind of character, the one that doesn't have a truly accurate vision of himself. It makes me laugh. Any of my foibles are born from my own hubris. Always, always. Anytime. I famously step in shit—at least for me it seems pretty epic. I often wind up with a smelly foot in my mouth. I often say the wrong thing, often in the wrong place and time. Often. In my own private Idaho, it's funny as shit. I don't have that gift. I'm better speaking in some other art form. I'm trying to get better. I'm really trying to get better.

And the movie really pokes at this, too, right—America's hubris? When I get in trouble it's because of my hubris. When America gets in trouble it's because of our hubris. We think we know better, and this idea of American exceptionalism—I think we're exceptional in many ways, I do, but we can't force it on others. We shouldn't think we can. How do we show American exceptionalism? By example. It's the same as being a good father. By exemplifying our tenets and our beliefs, freedom and choice and not closing borders and being protectionists. But that's another issue. You want me to tell you something really sad? I thought this was so sad. We were looking at—let me say, a certain war film that was looking to promote itself. The European posters had the American flag in the background, and it came back from the marketing department: “Remove the flag. It's not a good sell here.” I was, like, Man, that's America. That's what we've done to our brand.

You've played characters in pain. What is pain, emotional and physical? Yeah, I'm kind of done playing those. I think it was more pain tourism. It was still an avoidance in some way. I've never heard anyone laugh bigger than an African mother who's lost nine family members. What is that? I just got R&B for the first time. R&B comes from great pain, but it's a celebration. To me, it's embracing what's left. It's that African woman being able to laugh much more boisterously than I've ever been able to.

“For me this period has been about looking at my weaknesses and failures and owning my side of the street.”

When did you have that revelation? What have you been listening to? I've been listening to a lot of Frank Ocean. I find this young man so special. Talk about getting to the raw truth. He's painfully honest. He's very, very special. I can't find a bad one.

And of great irony to me: Marvin Gaye's Here, My Dear [Gaye's touchstone album about divorce]. And that kind of sent me down a road.

Intense. But beautiful—and quite honest.... You know, I just started therapy. I love it, I love it. I went through two therapists to get to the right one.

About These Parks: To choose the locations for this summertime celebration of America’s national parks, Brad Pitt, Ryan McGinley, and GQ Style all collaborated on potential destinations. Pitt requested the lunar dunes of White Sands National Monument. Ryan McGinley had previous experience shooting in the underground labyrinths of Carlsbad Caverns National Park. And we nominated the swamps of Everglades National Park. Then we came together and covered all three over a stretch of eight days in March.

Do you think if the past six months hadn't happened you'd be in this place eventually? That it would have caught up with you? I think it would have come knocking, no matter what.

People call it a midlife crisis, but this isn't the same— No, this isn't that. I interpret a midlife crisis as a fear of growing old and fear of dying, you know, going out and buying a Lamborghini. [pause] Actually—they've been looking pretty good to me lately! [laughs]

There might be a few Lamborghinis in your future! “I do have a Ford GT,” he says quietly. [laughs] I do remember a few spots along the road where I've become absolutely tired of myself. And this is a big one. These moments have always been a huge generator for change. And I'm quite grateful for it. But me, personally, I can't remember a day since I got out of college when I wasn't boozing or had a spliff, or something. Something. And you realize that a lot of it is, um—cigarettes, you know, pacifiers. And I'm running from feelings. I'm really, really happy to be done with all of that. I mean I stopped everything except boozing when I started my family. But even this last year, you know—things I wasn't dealing with. I was boozing too much. It's just become a problem. And I'm really happy it's been half a year now, which is bittersweet, but I've got my feelings in my fingertips again. I think that's part of the human challenge: You either deny them all of your life or you answer them and evolve.

Was it hard to stop smoking pot? No. Back in my stoner days, I wanted to smoke a joint with Jack and Snoop and Willie. You know, when you're a stoner, you get these really stupid ideas. Well, I don't want to indict the others, but I haven't made it to Willie yet.

I'm sure he's out there on a bus somewhere waiting for you. How about alcohol—you don't miss it? I mean, we have a winery. I enjoy wine very, very much, but I just ran it to the ground. I had to step away for a minute. And truthfully I could drink a Russian under the table with his own vodka. I was a professional. I was good.

So how do you just drop it like that? Don't want to live that way anymore.

What do you replace it with? Cranberry juice and fizzy water. I've got the cleanest urinary tract in all of L.A., I guarantee you! But the terrible thing is I tend to run things into the ground. That's why I've got to make something so calamitous. I've got to run it off a cliff.

Do you think that's a thing? I do it with everything, yeah. I exhaust it, and then I walk away. I've always looked at things in seasons, compartmentalized them, I guess, seasons or semesters or tenures or…

Really? So, this is the season of me getting my drink on.… [laughs] Yeah, it's that stupid. “This is my Sid and Nancy season.” I remember that one when I first got out to L.A. It got titled afterwards.

So then, you stop yourself, but how do you—I don't know why this comes to mind but I think of a house—how do you renovate yourself? Yeah, you start by removing all the decor and decorations, I think. You get down to the structure. Wow, we are in some big metaphor here now.… [laughs]

Inside Brad Pitt’s GQ Style Cover Shoot

Metaphors are my life. You strip down to the foundation and break out the mortar. I don't know. For me this period has really been about looking at my weaknesses and failures and owning my side of the street. I'm an asshole when it comes to this need for justice. I don't know where it comes from, this hollow quest for justice for some perceived slight. I can drill on that for days and years. It's done me no good whatsoever. It's such a silly idea, the idea that the world is fair. And this is coming from a guy who hit the lottery, I'm well aware of that. I hit the lottery, and I still would waste my time on those hollow pursuits.

That's the thing about becoming un-numb. You have to stare down everything that matters to you. That's it! Sitting with those horrible feelings, and needing to understand them, and putting them into place. In the end, you find: I am those things I don't like. That is a part of me. I can't deny that. I have to accept that. And in fact, I have to embrace that. I need to face that and take care of that. Because by denying it, I deny myself. I am those mistakes. For me every misstep has been a step toward epiphany, understanding, some kind of joy. Yeah, the avoidance of pain is a real mistake. It's the real missing out on life. It's those very things that shape us, those very things that offer growth, that make the world a better place, oddly enough, ironically. That make us better.

Would there be art without it? Would there be any of this immense beauty that surrounds us? Yeah—immense beauty, immense beauty. And by the way: There's no love without loss. It's a package deal.

Can you describe where you've been living—like, have you been in this house since September? It was too sad to be here at first, so I went and stayed on a friend's floor, a little bungalow in Santa Monica. I crashed over here a little bit, my friend [David] Fincher lives right here. He's always going to have an open door for me, and I was doing a lot of stuff on the Westside, so I stayed at my friend's house on the floor for a month and a half—until I was out there one morning, 5:30, and this surveillance van pulls up. They don't know that I'm up behind a wall, and they pull up—and it's a long story—but it was something more than TMZ, because they got into my friend's computer. The stuff they can do these days.... So I got a little paranoid being there. I decided I had to pick up and come here.

“If I'm not creating something, putting it out there, then I'll just be creating scenarios of fiery demise in my mind.”

How are your days different now? This house was always chaotic and crazy, voices and bangs coming from everywhere, and then, as you see, there are days like this: very…very solemn. I don't know. I think everyone's creative in some way. If I'm not creating something, doing something, putting it out there, then I'll just be creating scenarios of fiery demise in my mind. You know, a horrible end. And so I've been going to a friend's sculpting studio, spending a lot of time over there. My friend [Thomas Houseago] is a serious sculptor. They've been kind. I've literally been squatting in there for a month now. I'm taking a shit on their sanctity.

So you're making stuff? Yeah, I'm making stuff. It's something I've wanted to do for ten years.

Like what? What are you working with? I'm making everything. I'm working with clay, plaster, rebar, wood. Just trying to learn the materials. You know, I surprise myself. But it's a very, very lonely occupation. There's a lot of manual labor, which is good for me right now. A lot of lugging clay around, chopping and moving and cleaning up after yourself. But I surprise myself. Yesterday I wasn't settled. I had a lotta chaotic thoughts—trying to make sense of where we are at this time—and the thing I was doing wasn't controlled and balanced and perfect. It came out chaotic. I find vernacular in what you can make, rather than giving a speech. I find voice there, that I need.

All the bad stuff: Do you use it to tell your story? It just keeps knocking. I'm 53 and I'm just getting into it. These are things I thought I was managing very well. I remember literally having this thought a year, a year and a half ago, someone was going through some scandal. Something crossed my path that was a big scandal—and I went, “Thank God I'm never going to have to be a part of one of those again.” I live my life, I have my family, I do my thing, I don't do anything illegal, I don't cross anyone's path. What's the David Foster Wallace quote? Truth will set you free, but not until it's done with you first.

Is the sculpting a Sisyphean thing: rolling the rock up the hill, action obliterating all thoughts? [Jacques interrupts, nuzzling] I know you've been lonely. I know you've been lonely....

I find it the opposite. Well, I guess so, in that there's a task at hand. You have to wrap your stuff up at night and bring order back to your chaos for the next day. I find it a great opportunity for the introspection. Now you have to be real careful not to go too far that way and get cut off in that way. I'm really good at cutting myself off, and it's been a problem. I need to be more accessible, especially to the ones I love.

When you go dark, do you retreat, disconnect? I don't know how to answer that. I certainly shield. Shield, shield, shield. Mask, escape. Now I think: That's just me.

You were talking about the Glen character in War Machine and the idea of delusion, that we have to create our own mythologies, our own stories, to explain the things we're not proud of. At a real cost to ourselves.

How do you not delude yourself? I worry about that— You don't have to worry about it. [laughs] Delusion is not going to let you go. You're going to get smacked in the face. We, as humans, construct such mousetrap mind games to get away from it all. You know, we're almost too smart for ourselves.

Okay. But if you had a slideshow of all your worst moments as a human, you wouldn't want anyone to see that slideshow. The way you've had to live for years, that slideshow has been public. But so little of it is accurate, and I avoid so much of it. I just let it go. It's always been a long-run game for me. As far as out there, I hope my intentions and work will speak for themselves. But, yes, at the same time, it is a drag to have certain things drug out in public and misconstrued. I worry about it more for my kids, being subjected to it, and their friends getting ideas from it. And of course it's not done with any kind of delicacy or insight—it's done to sell. And so you know the most sensational sells, and that's what they'll be subjected to, and that pains me. I worry more in my current situation about the slideshow my kids have. I want to make sure it's well-balanced.

“People on their deathbeds don't talk about what they obtained. They talk about their loved ones or their regrets—that seems to be the menu.”

How do you make sense of the past six months and keep going? Family first. People on their deathbeds don't talk about what they obtained or were awarded. They talk about their loved ones or their regrets—that seems to be the menu. I say that as someone who's let the work take me away. Kids are so delicate. They absorb everything. They need to have their hand held and things explained. They need to be listened to. When I get in that busy work mode, I'm not hearing. I want to be better at that.

When you begin making a family, I think you hope to create another family that is some ideal mix of the best of what you had and what you feel you didn't have— I try to put these things in front of them, hoping they'll absorb it and that it will mean something to them later. Even in this place, they won't give a shit about that little bust over there or that light. They won't give a shit about that inlay, but somewhere down the road it will mean something—I hope that it will soak in.

It's a different world, too. We know more, we're more focused on psychology. I come from a place where, you know, it's strength if we get a bruise or cut or ailment we don't discuss it, we just deal with it. We just go on. The downside of that is it's the same with our emotion. I'm personally very retarded when it comes to taking inventory of my emotions. I'm much better at covering up. I grew up with a Father-knows-best/war mentality—the father is all-powerful, super strong—instead of really knowing the man and his own self-doubt and struggles. And it's hit me smack in the face with our divorce: I gotta be more. I gotta be more for them. I have to show them. And I haven't been great at it.

Do you know, specifically, logistically when you have the kids? Yeah. We're working at that now.

It must be much harder when visitation is uncertain— It was all that for a while. I was really on my back and chained to a system when Child Services was called. And you know, after that, we've been able to work together to sort this out. We're both doing our best. I heard one lawyer say, “No one wins in court—it's just a matter of who gets hurt worse.” And it seems to be true, you spend a year just focused on building a case to prove your point and why you're right and why they're wrong, and it's just an investment in vitriolic hatred. I just refuse. And fortunately my partner in this agrees. It's just very, very jarring for the kids, to suddenly have their family ripped apart.

That's what I was going to ask— If anyone can make sense of it, we have to with great care and delicacy, building everything around that.

How do you tell your kids? Well, there's a lot to tell them because there's understanding the future, there's understanding the immediate moment and why we're at this point, and then it brings up a lot of issues from the past that we haven't talked about. So our focus is that everyone comes out stronger and better people—there is no other outcome.

“I know I'm just in the middle of this thing now—not at the beginning or at the end, just smack-dab in the middle. And I don't want to dodge any of it.”

And the fact that you guys are pointing toward that—that clearly doesn't always happen. If you ended up in court, it would be a spectacular nightmare. Spectacular. I see it everywhere. Such animosity and bitterly dedicating years to destroying each other. You'll be in court and it'll be all about affairs and it'll be everything that doesn't matter. It's just awful, it looks awful. One of my favorite movies when it came out was There Will Be Blood, and I couldn't figure out why I loved this movie, I just loved this movie, besides the obvious talent of Paul T. and, you know, Daniel Day. But the next morning I woke up, and I went, Oh, my God, this whole movie is dedicated to this man and his hatred. It's so audacious to make a movie about it, and in life I find it just so sickening. I see it happen to friends—I see where the one spouse literally can't tell their own part in it, and is still competing with the other in some way and wants to destroy them and needs vindication by destruction, and just wasting years on that hatred. I don't want to live that way.

What in the past week has given you immense joy? Can you feel that right now? It's an elusive thing. It's been a more painful week than normal—just certain things have come up—but I see joy out the window, and I can see the silhouette of palms and an expression on one of my kids' faces, a parting smile, or finding some, you know, moment of bliss with the clay. You know, it's everywhere, it's got to be found. It's the laughter of the African mother in my experience—it's got to come from the blues, to get R&B. That'll be in my book.

Are you going to write a book? No! I find writing too arduous.

But do you worry about the narrative others have written for you? What did Churchill say? History will be kind to me: I know because I'll write it myself. I don't really care about protecting the narrative. That's when I get a bit pessimistic, I get in my oh-it-all-goes-away-anyway kind of thinking. But I know the people who love me know me. And that's enough for me.

Do you remember your dreams? Yeah. A few months ago I was having frightening dreams and I'd consciously lie awake trying to ask, What can I get out of this? What can I learn from this? Those ceased. And now I have been having moments of joy, and you wake and realize it's just a dream, and I get a bit depressed for the moment. Just the moment, just glimpse moments of joy because I know I'm just in the middle of this thing now and I'm not at the beginning of it or at the end of it, just where this chapter is right now, just smack-dab in the middle. It's fucking in the middle of it and, you know, I just don't want to dodge any of it. I just want to stand there, shirt open, and take my hits and see, and see.

There's obviously incredible grief. This is like a death— Yeah.

There's a process— Yeah, I think for everyone, for the kids, for me, absolutely.

So is there an urge to try to— The first urge is to cling on.

Then? And then you've got a cliché: “If you love someone, set them free.” Now I know what it means, by feeling it. It means to love without ownership. It means expecting nothing in return. But it sounds good written. It sounds good when Sting sings it. It doesn't mean fuck-all to me until, you know—

Until you can embody it. Until you live it. That's why I never understood growing up with Christianity—don't do this, don't do that—it's all about don'ts, and I was like how the fuck do you know who you are and what works for you if you don't find out where the edge is, where's your line? You've got to step over it to know where it is.

For the photo shoot you went to three national parks in a week. It sounds like a boondoggle. What's the definition of a boondoggle?

I think of it as a sort of ridiculous adventure— Sounds very Ozarkian. Like something I should know but I don't. Yeah, it was great. Ryan [McGinley, the photographer] had us jumping in the Everglades, you know, like gators. I figured, Well, if they do it on Naked and Afraid, I can do it. But they had the old wrangler, he's got his snake pole and it's got this grabber, like something Grandma would use to pick something off the top shelf, but fine. He took a little walk-through, and if he didn't get eaten, then reportedly I wouldn't get eaten. At least that was the logic behind it all, but he said to me, “When you get to be my age, never pass up a bathroom. Never trust a fart. And never waste a boner.”

Whoa. Then White Sands? I've never seen anything like it. I mean the dunes are so sculptural and modern and simple and vast and just incredible shapes. To see them white and reflecting white—the sky's actually darker than that ground. It's an odd, beautiful place.

And then the third? We did Carlsbad Caverns. If we're going to do a celebrity shoot, let's make something, work with an artist, see what we come up with. It's always more interesting.

After all this, do you feel constrained as an actor in some ways? No, I don't really think of myself much as an actor anymore. It takes up so little of my year and my focus. Film feels like a cheap pass for me, as a way to get at those hard feelings. It doesn't work anymore, especially being a dad.

On the pie chart, what is acting? Acting would be very small slice.

Do you see yourself as having been successful? I wish I could just change my name.

Come out as a new person? Like P. Diddy. I can be Puffy now or—what is Snoop? Lion? I just felt like Brad was a misnomer, and now I just feel like fucking Brad.

What other name would you have put on yourself? Nothing. When outside success comes, the thing I've enjoyed the most is when there's a personal discovery in it. But when I find it repetitious or painfully boring, it's absolute death to me.

When you're talking, you kinda rub your thumb against your fingers a lot—it's just an observation. I don't know. I'm tactile—I'm a tactile individual. “I like to feel things up,” he said. [laughs]

Yeah, in high school he was the boy voted most likely to— To feel you up. [laughs] I don't know, I guess it's back to feeling. I think I spent a lot of time avoiding feelings and building structures, you know, around feelings. And now I have no time left for that.

When is the acting still exciting? I would say more in comedic stuff, where you're taking gambles. I can turn out the hits over and over and I just—my favorite movie is the worst-performing film of anything I've done, The Assassination of Jesse James. If I believe something is worthy, then I know it will be worthy in time to come. And there are times I get really cynical, you know. I spend a lot of time on design and even this sculpture folly I'm on, I have days when—it all ends up in the dirt anyways: What's the point? So I go through that cycle, too, you know? What's the point?

Oh man, that's a big question. I know what the point is—it's communicating, it's connecting. I believe we're all cells in one body; we're all part of the same construct. Although a few of us are cancerous. It's helping others. Yeah, we help each other, that's it.

So what's on the agenda later? I'm anxious to get to the studio. I think it was Picasso who talked about the moment of looking at the subject, and paint hitting canvas, and that is where art happens. For me I'm having a moment of getting to feel emotion at my fingertips. But to get that emotion to clay—I just haven't cracked the surface. And I don't know what's coming. Right now I know the manual labor is good for me, getting to know the expansiveness and limitations of the materials. I've got to start from the bottom, I've got to sweep my floor, I've got to wrap up my shit at night, you know?

A metaphor again. But it works. Right now I've got to hammer my own nails.

Michael Paterniti is a GQ correspondent. This is his first piece for GQ Style.

This story appears in the Summer 2017 issue of GQ Style with the title “Monumental.””

#GQ style#brad pitt#ryan mcginlley#carlsbad caverns#white sands#everglades#interview#fashion#clothes#clothing#Valentino#Eyevan#miansai#junya watanabe#comme des garcons#giorgio armani#bottega veneta#rick owens#david yurman#missoni#rag & bone#brunello cucinelli#tudor#dior homme#dior#hublot#ralph lauren#louis vuitton#Ermenegildo Zegna#Dries Van Noten

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

18th December >> (@zenitenglish) #PopeFrancis #Pope Francis Message for 52nd World Day of Peace ‘Good politics at the service of peace’.

Pope’s Message for 52nd World Day of Peace

‘Good politics at the service of peace’

Below is the Vatican-provided text of Pope Francis’ Message for the 52nd World Day of Peace, which is celebrated on January 1st, on the theme: ‘Good politics at the service of peace:’

***

Good politics at the service of peace

1. “Peace be to this house!”

In sending his disciples forth on mission, Jesus told them: “Whatever house you enter, first say, ‘Peace be to this house!’ And if a son of peace is there, your peace shall rest upon him; but if not, it shall return to you” (Lk 10:5-6).

Bringing peace is central to the mission of Christ’s disciples. That peace is offered to all those men and women who long for peace amid the tragedies and violence that mark human history.[1] The “house” of which Jesus speaks is every family, community, country and continent, in all their diversity and history. It is first and foremost each individual person, without distinction or discrimination. But it is also our “common home”: the world in which God has placed us and which we are called to care for and cultivate.

So let this be my greeting at the beginning of the New Year: “Peace be to this house!”

2. The challenge of good politics

Peace is like the hope which the poet Charles Péguy celebrated.[2] It is like a delicate flower struggling to blossom on the stony ground of violence. We know that the thirst for power at any price leads to abuses and injustice. Politics is an essential means of building human community and institutions, but when political life is not seen as a form of service to society as a whole, it can become a means of oppression, marginalization and even destruction.

Jesus tells us that, “if anyone would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all” (Mk 9:35). In the words of Pope Paul VI, “to take politics seriously at its different levels – local, regional, national and worldwide – is to affirm the duty of each individual to acknowledge the reality and value of the freedom offered him to work at one and the same time for the good of the city, the nation and all mankind”.[3]

Political office and political responsibility thus constantly challenge those called to the service of their country to make every effort to protect those who live there and to create the conditions for a worthy and just future. If exercised with basic respect for the life, freedom and dignity of persons, political life can indeed become an outstanding form of charity.

3. Charity and human virtues: the basis of politics at the service of human rights and peace

Pope Benedict XVI noted that “every Christian is called to practise charity in a manner corresponding to his vocation and according to the degree of influence he wields in the pólis… When animated by charity, commitment to the common good has greater worth than a merely secular and political stand would have… Man’s earthly activity, when inspired and sustained by charity, contributes to the building of the universal city of God, which is the goal of the history of the human family”.[4] This is a programme on which all politicians, whatever their culture or religion, can agree, if they wish to work together for the good of the human family and to practise those human virtues that sustain all sound political activity: justice, equality, mutual respect, sincerity, honesty, fidelity.

In this regard, it may be helpful to recall the “Beatitudes of the Politician”, proposed by Vietnamese Cardinal François-Xavier Nguyễn Vãn Thuận, a faithful witness to the Gospel who died in 2002:

Blessed be the politician with a lofty sense and deep understanding of his role. Blessed be the politician who personally exemplifies credibility. Blessed be the politician who works for the common good and not his or her own interest. Blessed be the politician who remains consistent. Blessed be the politician who works for unity. Blessed be the politician who works to accomplish radical change. Blessed be the politician who is capable of listening. Blessed be the politician who is without fear.[5]

Every election and re-election, and every stage of public life, is an opportunity to return to the original points of reference that inspire justice and law. One thing is certain: good politics is at the service of peace. It respects and promotes fundamental human rights, which are at the same time mutual obligations, enabling a bond of trust and gratitude to be forged between present and future generations.

4. Political vices

Sadly, together with its virtues, politics also has its share of vices, whether due to personal incompetence or to flaws in the system and its institutions. Clearly, these vices detract from the credibility of political life overall, as well as the authority, decisions and actions of those engaged in it. These vices, which undermine the ideal of an authentic democracy, bring disgrace to public life and threaten social harmony. We think of corruption in its varied forms: the misappropriation of public resources, the exploitation of individuals, the denial of rights, the flouting of community rules, dishonest gain, the justification of power by force or the arbitrary appeal to raison d’état and the refusal to relinquish power. To which we can add xenophobia, racism, lack of concern for the natural environment, the plundering of natural resources for the sake of quick profit and contempt for those forced into exile.

5. Good politics promotes the participation of the young and trust in others

When the exercise of political power aims only at protecting the interests of a few privileged individuals, the future is compromised and young people can be tempted to lose confidence, since they are relegated to the margins of society without the possibility of helping to build the future. But when politics concretely fosters the talents of young people and their aspirations, peace grows in their outlook and on their faces. It becomes a confident assurance that says, “I trust you and with you I believe” that we can all work together for the common good. Politics is at the service of peace if it finds expression in the recognition of the gifts and abilities of each individual. “What could be more beautiful than an outstretched hand? It was meant by God to offer and to receive. God did not want it to kill (cf. Gen 4:1ff) or to inflict suffering, but to offer care and help in life. Together with our heart and our intelligence, our hands too can become a means of dialogue”.[6]

Everyone can contribute his or her stone to help build the common home. Authentic political life, grounded in law and in frank and fair relations between individuals, experiences renewal whenever we are convinced that every woman, man and generation brings the promise of new relational, intellectual, cultural and spiritual energies. That kind of trust is never easy to achieve, because human relations are complex, especially in our own times, marked by a climate of mistrust rooted in the fear of others or of strangers, or anxiety about one’s personal security. Sadly, it is also seen at the political level, in attitudes of rejection or forms of nationalism that call into question the fraternity of which our globalized world has such great need. Today more than ever, our societies need “artisans of peace” who can be messengers and authentic witnesses of God the Father, who wills the good and the happiness of the human family.

6. No to war and to the strategy of fear

A hundred years after the end of the First World War, as we remember the young people killed in those battles and the civilian populations torn apart, we are more conscious than ever of the terrible lesson taught by fratricidal wars: peace can never be reduced solely to a balance between power and fear. To threaten others is to lower them to the status of objects and to deny their dignity. This is why we state once more that an escalation of intimidation, and the uncontrolled proliferation of arms, is contrary to morality and the search for true peace. Terror exerted over those who are most vulnerable contributes to the exile of entire populations who seek a place of peace. Political addresses that tend to blame every evil on migrants and to deprive the poor of hope are unacceptable. Rather, there is a need to reaffirm that peace is based on respect for each person, whatever his or her background, on respect for the law and the common good, on respect for the environment entrusted to our care and for the richness of the moral tradition inherited from past generations.

Our thoughts turn in a particular way to all those children currently living in areas of conflict, and to all those who work to protect their lives and defend their rights. One out of every six children in our world is affected by the violence of war or its effects, even when they are not enrolled as child soldiers or held hostage by armed groups. The witness given by those who work to defend them and their dignity is most precious for the future of humanity.

7. A great project of peace

In these days, we celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in the wake of the Second World War. In this context, let us also remember the observation of Pope John XXIII: “Man’s awareness of his rights must inevitably lead him to the recognition of his duties. The possession of rights involves the duty of implementing those rights, for they are the expression of a man’s personal dignity. And the possession of rights also involves their recognition and respect by others”.[7]

Peace, in effect, is the fruit of a great political project grounded in the mutual responsibility and interdependence of human beings. But it is also a challenge that demands to be taken up ever anew. It entails a conversion of heart and soul; it is both interior and communal; and it has three inseparable aspects:

– peace with oneself, rejecting inflexibility, anger and impatience; in the words of Saint Francis de Sales, showing “a bit of sweetness towards oneself” in order to offer “a bit of sweetness to others”;

– peace with others: family members, friends, strangers, the poor and the suffering, being unafraid to encounter them and listen to what they have to say;

– peace with all creation, rediscovering the grandeur of God’s gift and our individual and shared responsibility as inhabitants of this world, citizens and builders of the future.

The politics of peace, conscious of and deeply concerned for every situation of human vulnerability, can always draw inspiration from the Magnificat, the hymn that Mary, the Mother of Christ the Saviour and Queen of Peace, sang in the name of all mankind: “He has mercy on those who fear him in every generation. He has shown the strength of his arm; he has scattered the proud in their conceit. He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly; …for he has remembered his promise of mercy, the promise he made to our fathers, to Abraham and his children for ever” (Lk 1:50-55).

From the Vatican, 8 December 2018

FRANCIS

_________________________

[1] Cf. Lk 2:14: “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among men with whom he is pleased”. [2] Cf. Le Porche du mystère de la deuxième vertu, Paris, 1986. [3] Apostolic Letter Octogesima Adveniens (14 May 1971), 46. [4] Encyclical Letter Caritas in Veritate (29 June 2009), 7. [5] Cf. Address at the “Civitas” Exhibition-Convention in Padua: “30 Giorni”, no. 5, 2002. [6] BENEDICT XVI, Address to the Authorities of Benin, Cotonou, 19 November 2011. [7] Encyclical Letter Pacem in Terris (11 April 1963), ed. Carlen, 24.

[02049-EN.01] [Original text: Italian] [Vatican-provided text]DECEMBER 18, 2018 11:01

POPE AND HOLY SEE

0 notes